Return to Narnia: part I – The Magician’s Nephew

This post is part of a series revisiting my favourite childhood reads.

Of the whole Narnia sequence, the book I think of as my favourite is ‘The Magician’s Nephew’. This is despite, or perhaps because, it spends less time in Narnia than the other books. Rereading it was a very happy experience with some surprises along the way.

The biggest surprise was that it was funny, which isn’t a word I would have come up with unprompted before I started. There are some wonderful set pieces, especially the cab chase that piles up outside Uncle Andrew’s house.

‘The Magician’s Nephew’ is the sixth book that Lewis wrote (see Return to Narnia: prologue for a comment on reading order versus publication order) and I think that shows – it’s pacey and handles shifts in tone in a way that young readers will cope with. The fun of the chase scene is needed to offset what’s gone before.

But we need to rewind a bit here. ‘The Magician’s Nephew’ is the story of Digory (the nephew of the title) and Polly, who are caught up in Uncle Andrew’s experiments with magic. There are pairs of rings, one green and one yellow, that can transport people between worlds. The children visit the Wood between the Worlds which is an in-between place with pools that give access to multiple worlds. They end up in the ruined city of Charn where Digory breaks a spell and awakens Jadis. The children accidentally bring her back to their own time of Victorian London and chaos ensues. When they attempt to return her to her own world they encounter Aslan and witness the creation of Narnia. Jadis tries to tempt Digory in the garden but is unsuccessful. The children return home, Digory’s sick mother recovers thanks to a gift from Aslan, Uncle Andrew gives up magic and order is restored.

One of the frequent criticisms of C.S. Lewis is that he throws the kitchen sink at his children’s books – in other words, there are references taken from all sorts of source materials that don’t necessarily feel like they belong together. There are lots of things going on in ‘The Magican’s Nephew’ but they do seem to work together. Firstly, we have Victorian London with its horse-drawn cabs and lamp posts, Lewis points his readers to Edith Nesbit’s Bastable books and Sherlock Holmes on the first page so we know exactly what kind of world in which to ground Polly and Digory. (Lewis’ asides to his readers are of the kindly guide variety, rather than the condescending adult variety) On to this Victorian setting, Lewis adds fairytale elements – so we have a bad uncle, a sick mother and attics waiting to be explored; on to these he can then later add magic rings, talking animals, a wicked witch and other worlds. It’s very much a book that allows children to start somewhere familiar and gradually go somewhere very unfamiliar.

The Wood between the Worlds is the first of the fantasy worlds the children encounter. It’s a strange, quiet, enchanted place where the children almost forget who they are and how they got there.

You could almost feel the trees growing…. You could almost feel the trees drinking the water up with their roots.

It’s the repeated ‘almost feel’ that conveys the atmosphere of the place so well. We’re also told that when Digory tries to describe it afterwards he reaches for ‘richness’ as his descriptor:

‘It was a rich place: as rich as plum cake.’

By contrast the quiet of the ruined city of Charn is ‘a dead, cold, empty silence’, this is an altogether more unsettling place and the atmosphere prepares the reader for the unlocking of the spell and the release of Jadis.

The walls rose very high all around that courtyard. They had many great windows in them, windows without glass, through which you saw nothing but black darkness. Lower down there were great pillared arches, yawning like the mouths of railway tunnels. It was rather cold.

After this it’s back to London for the cab chase that will end with Jadis breaking the lamp post that will one day welcome Lucy to Narnia, and will set the cabby and his horse on the way to important roles in the founding of Narnia.

And then, in chapter nine (page 97 in my edition) we finally come to the founding of Narnia. This is a fabulous chapter that consciously draws on an important source for Lewis, the Biblical account of creation found in Genesis 1-2.

In Genesis 1, the repeated refrain is ‘And God said…’, the whole of creation is spoken into existence. Lewis’ poetic twist is to have Aslan sing Narnia into being:

The Lion was pacing to and fro about that empty land and singing his new song.

And as he walked and sang the valley grew green with grass. It spread out from the Lion like a pool.

In Genesis 1:24 we have ‘And God said, let the earth bring forth the living creature after his kind…’ which is turned into a much more vibrant image:

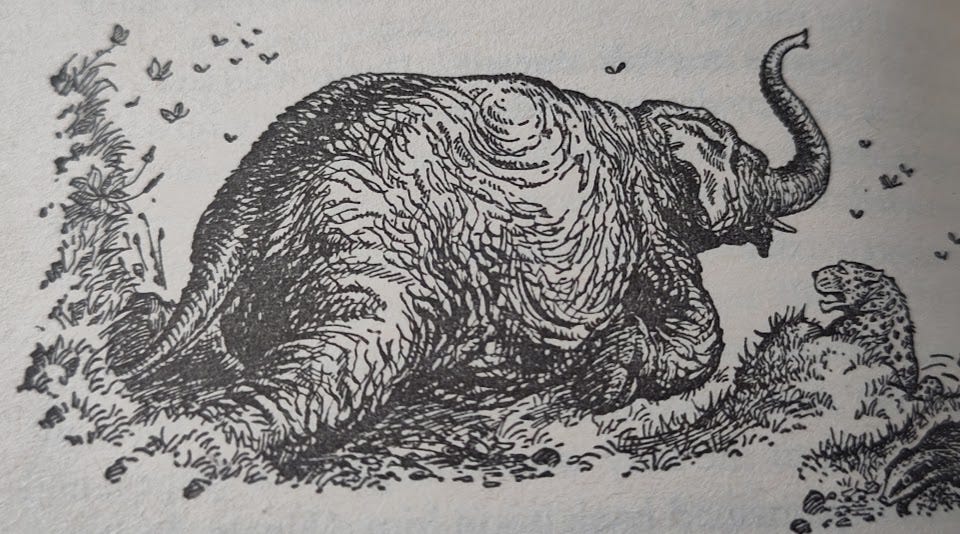

And the humps moved and swelled till they burst, and the crumbled earth poured out of them, and from each hump there came an animal.

This is the King James Version of the Bible reimagined for young readers. What happens next is perhaps particularly interesting for anyone with an interest in Biblical translation and / or ecotheology. [1]

Having made the cabby and his wife King and Queen of Narnia, Aslan says:

You shall rule and name all these creatures, and do justice among them, and protect them from their enemies when enemies will arise.

He goes on to ask:

Can you rule these creatures kindly and fairly, remembering that they are not slaves like the dumb beasts of the world you were born into, but Talking Beasts and free subjects?

Genesis 2 has God giving Adam the responsibility of naming the animals but it’s words like ‘rule’ and ‘dominion’ that have seen much ink spilt over Christian attitudes to nature and the environment. Genesis 2:15 in the KJV has ‘dress it and keep it’ when referring to the Garden of Eden, while the NIV has ‘work it and take care of it’ and modern readings will often emphasise stewardship and care rather than rule. So what Lewis does here, writing in the 1950s, is interesting. He’s emphasising justice, protection, kindness and fairness, values which when applied to animals feels quite modern in a theological sense. The contrast between ‘dumb beasts’ and ‘Talking Beasts’ might give readers pause for thought, but there’s an interesting sequence where Strawberry, the cabby’s horse, is allowed to give voice to complaints about ill treatment that perhaps sheds some more light on Lewis’ sympathies.

As I mentioned in my first post on Narnia, I’m rereading the Narnia books alongside Katherine Langrish’s book ‘From Spare Oom to War Drobe. Travels in Narnia with my Nine Year-Old Self.’ One of the elements she discusses is the subplot of Digory’s mother. We know she is very ill and likely to die. Digory’s desire to cure his mother and have her live drives the next part of the story where, and again the echoes of Genesis are clear, Jadis tempts him to steal the fruit that might save his mother. She does this in a garden. Jadis is the serpent but, unlike Eve, Digory resists and is rewarded.

This is what would have happened, child, with a stolen apple. It is not what will happen now. What I give you now will bring joy. It will not, in your world, give endless life, but it will heal.

And, sure enough, Digory gets his miracle. Young Jack (as he was known) Lewis on the other hand did not and lost his mother early. This is wish fulfilment on the part of the author but it also infuses the book, and Digory’s dilemma, with a complete believability. Lewis can write the bewildered and hurting child because he was him.

Langrish is, I think, correct in saying

Lewis has an extraordinary ability to engage his child readers in philosophical and moral questions at a level appropriate to their understanding without talking down.

‘The Magician’s Nephew’ sets up the next in the chronological sequence nicely – the elements of Narnia that Lucy will encounter when she walks through the wardrobe are in place, the tree that will provide the wood to build the wardrobe has been planted, the house that will hold that same wardrobe is waiting, Digory will grow up to be the professor. Of course this was all actually reverse engineering because ‘The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe’ was written first, but nonetheless, to this reader at least, ‘The Magician’s Nephew’ was, and is, a satisfying explanation of how Narnia came to be. It’s an intensely moral book with pacey storytelling, vivid worlds and a happy ending. As a child I believed in it utterly and as an adult I found being whisked back in time with it perhaps the most intensely comforting experience of any of the books I’ve reread for this series so far.

Next month – Return to Narnia: part II – The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe

[1] Broadly speaking, ecotheology is focused on the relationship between religion and nature, particularly with reference to contemporary environmental concerns. A practical outworking of that in the UK is the Eco Church programme run by A Rocha UK.

Of all the Narnia books this is the one which ties on with his Preface to Paradise Lost. One of the Science Fiction trilogy also does. Perelandra, no. 2 in the trilogy. (Are they any good? Nearly 60 years since I read them and don't have copies so can't say!)

The guinea pigs and other themes and elements of The Magician's Nephew reappear in Susanna Clarke's Piranesi. Which I liked a lot although not everyone does...

Both the Wood Between the Worlds and the earlier scene going through the attics fascinated me as a child. In my last re-read (-listen) I noticed that I know exactly what every scene in this book LOOKS like. It goes well beyond the illustrations, and none of the film adaptations ever got this far, so it must be entirely attributable to the writing!

Have you read Nesbit's 'Story of the Amulet'? While Lewis mentions the Bastables, it seems a stronger influence: the main characters visit different worlds in search of an artefact that will cure their mother, and the Queen of Babylon sequence is an obvious precursor to Jadis in London.