I fell over a reference to Vera Brittain’s 1950 work In The Steps of John Bunyan. An Excursion into Puritan England while researching a piece on the seventeenth century writer and preacher. Intrigued, I tracked down a copy of the 1980s reprint, published to mark the tercentenary of Bunyan’s death which fell in 1988.

Vera Brittain is probably best known as the author of The Testament of Youth, a memoir published in 1933, which detailed her experiences during World War One. She had begun reading English at Somerville College, Oxford, but broke off her studies in 1915 to serve as a Voluntary Aid Detachment nurse. Her fiancé, a number of her close friends, and her brother were all killed during the war. She returned to Oxford in 1919, this time to read history, and in In The Steps of John Bunyan we meet Vera Brittain the historian.

John Bunyan was born in Elstow, near Bedford, in 1628. He attended the local school before following his father’s trade as an itinerant tinker, mending pans and other metal utensils, and becoming familiar with many of Bedfordshire’s tracks, roads and footpaths. In 1644 he joined Oliver Cromwell’s Parliamentary forces and was garrisoned at Newport Pagnell. He served for three years before leaving the army and returning to Elstow. After a period of spiritual struggle he joined an independent congregation in Bedford, becoming a popular local preacher and prolific theological writer. Today he is principally remembered as the author of The Pilgrim’s Progress (1678), an allegorical work capturing his vision of the Christian journey through life, and for the long periods of imprisonment he faced for refusing to compromise his non-conformist beliefs. He died in 1688, after contracting a fever while riding from Reading to London in heavy rain. He is buried in Bunhill Fields, the Dissenters burial ground in Finsbury.

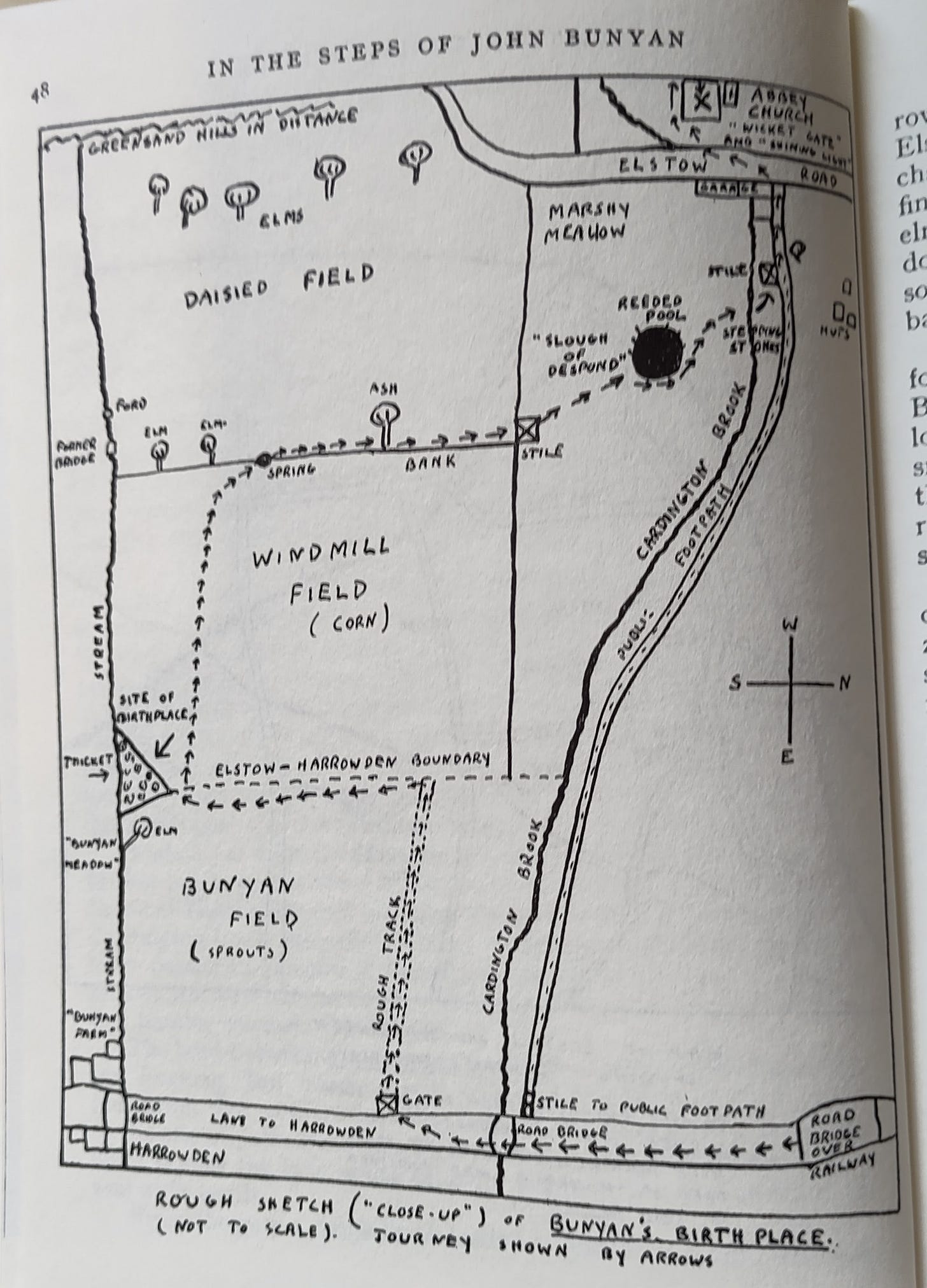

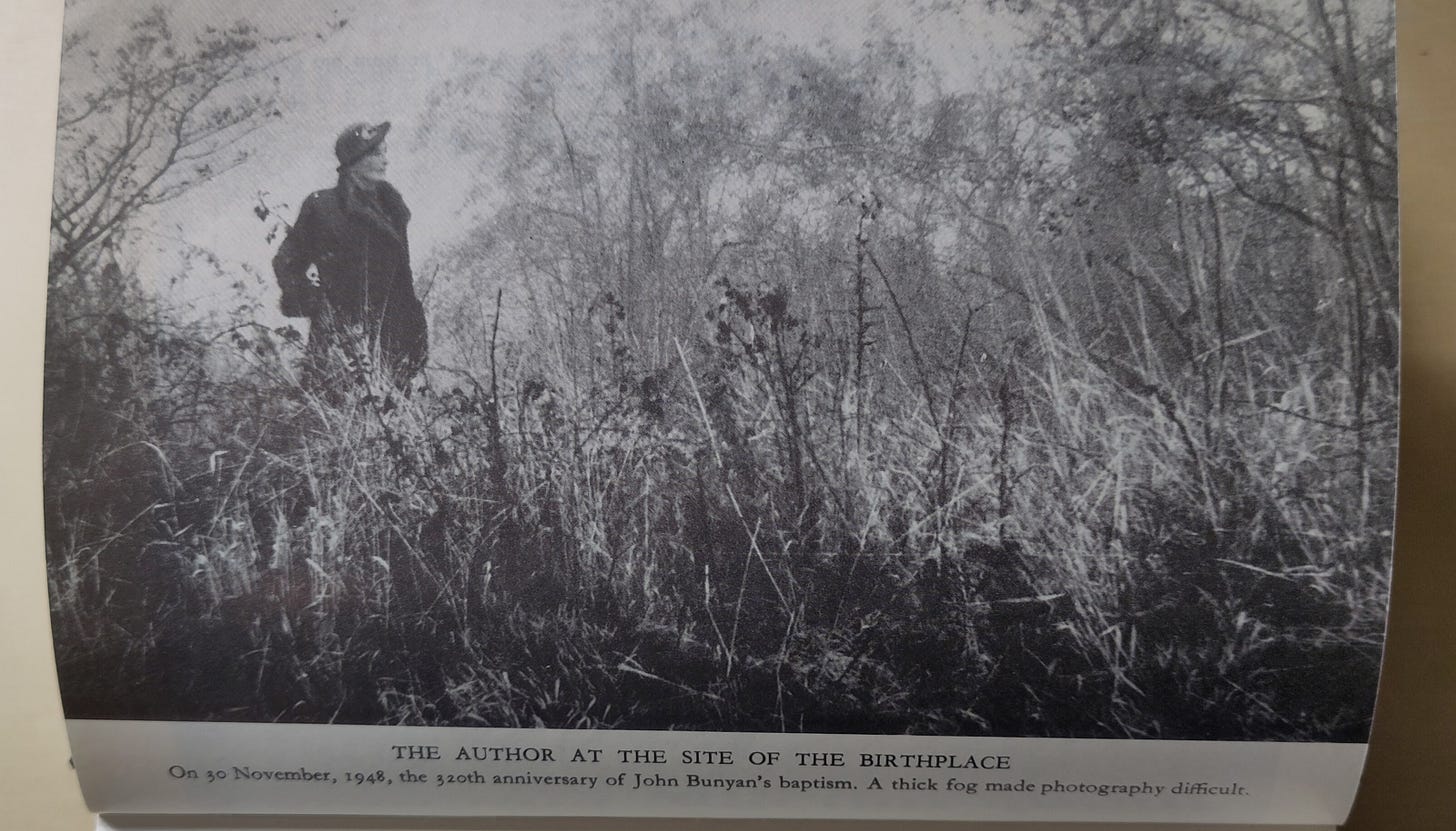

Brittain’s main contention is that understanding Bunyan involves understanding the world in which he lived, both in terms of the historical context and the places he knew. This makes for an interesting book that cannot quite decide what it wants to be. It’s part history, part biography, part literary criticism and part literary and religious pilgrimage. Brittain’s commitment to on the ground research lifts the book – there are photographs, sketch maps and accounts of her walks and visits. Her personal experience of Bunyan’s Bedfordshire and efforts to recreate his lost world provide some of the most vivid and immediate passages of the book. However, Brittain also knows how to tell a good story so the biographical and historical material that makes up the bulk of the book is also eminently readable.

It’s very clear that Brittain deeply admires both Bunyan the man and The Pilgrim’s Progress. Early on she describes herself as a ‘Quaker-inclined Anglican married to a Catholic, and hence, I hope, free from the impulse to grind any denominational axe’. She reiterates Bunyan’s commitment to freedom of conscience over any particular form of theology, despite his personal convictions. She criticises past biographers for either over focusing on Bunyan’s piety or making him a ‘species of village idiot’, whilst

They have analysed The Pilgrim’s Progress until, if it were not indestructible, it would have perished from analysis.

The admiration occasionally spills over into something more akin to hero worship which can be a bit eyebrow raising in places. What is clear though, is that Brittain expects her readers to be onside in admiration. This is one of the striking things about the book – the gap between 1950 and now, both in terms of the likelihood of readers being familiar with The Pilgrim’s Progress, and perhaps more crucially its Biblical source material; and the descriptions of Bedford and Bedfordshire.

At Harrowden, my search for the site of John Bunyan’s long-vanished birthplace, marked by no memorial, involved an undirected waist-deep plunge through a field of Brussels sprouts. At Stevington, the technically illegal attempt to locate the old Non-conformist baptising place in The Holmes Wood beside the Ouse meant a battle with briars and brambles in which my clothes were the losers, though I found the place in the end.

A memorial was erected at Harrowden not long after the publication of the book as part of the Festival of Britain celebrations in 1951. Brittain would probably have approved of other improvements to the way Bunyan is memorialised in his home county, including a new John Bunyan Museum in Bedford which opened in 1998 and the conversion of the Moot Hall in Elstow into a museum of seventeenth century rural life. She may have looked less kindly on some of the changes to the landscape brought about by increasing development post 1950.

Some sections of the book are infused with a very particular kind of patriotic nostalgia, born of the two recent World Wars.

During the past thirty years the hearts of British men and women have repeatedly been broken by calamity, but their spirit, like John Bunyan’s, has never been defeated.

This is perhaps especially evident when Brittain visits Bunyan’s grave in Bunhill Fields and sees the bomb damage to his grave, and when she considers England as a whole:

This England of John Bunyan is the England of us all; it is yours and mine. We are the privileged inheritors of the green mellow land, rich in traditions and memories, which neither war nor revolution has yet destroyed.

In many ways then, this book is as much about the period of Vera Brittain’s life as it is about John Bunyan’s, which makes it of interest twice over to modern historians. After her experiences in the First World War, Brittain became a pacifist, committed to the peace movement and a regular speaker for the League of Nations Union which supported the goals of collective security, disarmament and settling international disputes through negotiation and arbitration. Understanding this is key to understanding some of the ways in which Brittain talks about conflict and country in the seventeenth century.

I most enjoyed In The Steps of John Bunyan when Brittain interrupted the narrative to share her experiences of following in Bunyan’s footsteps, whether in Bedford, its surrounding villages and countryside, or in London. At these points it becomes something more personal – a kind of travel book that could be either a religious, literary or historical pilgrimage.

Sparrows and finches twitter in the elders and hazels which cluster beside the stream. Brown dragonflies dart in elusive zig-zags from bank to bank […] Across the stream lies the open stretch of ploughland and green fields which have hardly changed since John Bunyan saw them through the little leaded panes of his bedroom window.

This first hand knowledge also infuses the more descriptive passages in her telling of Bunyan’s story, helping to bring the world of seventeenth century England to life.

In the end, this is a very human book. There is a real sense of John Bunyan as an individual, as a soldier, as a man wrestling with his faith, as a husband and father, and as a man of conscience. Vera Brittain is also present, her personality springs off the page – if it didn’t this would have been a very different, and much less interesting, book.

I have to admit that, despite being a Bedfordshire resident, I have never read Bunyan, Bedford seems to distant! VB ‘Testament of Youth’ I read in my teens and loved it, revisited it in my 30s and never finished it. I have now added both of these books to my wish list! Thank you!

I've walked the Bedfordshire bit of the Icknield Way, which was so beautiful. I think it will be worth going back and walking some Bunyan paths. I wonder if it's changed very much since Brittain walked there?