Return to Narnia: part IV – Prince Caspian

Three things I liked.

When the BBC adapted Prince Caspian in the 1980s, they combined it with The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, giving two episodes to Prince Caspian and four to The Voyage of the Dawn Treader. As a result, the two books have been fused together in my mind, along with a general feeling that Caspian is the book you need to get through in order to reach Voyage. I toyed with combining the two rereads into one but, in the end, a desire to encounter Caspian on its own terms won out.

The plot is fairly straightforward, featuring a young prince battling for his rightful inheritance in the face of a usurping and murderous uncle. The magic of Old Narnia has been suppressed, Miraz is a cruel ruler, taxes are high and the law is strict. The Pevensie children are summoned back to Narnia, pulled from a railway station platform when Caspian blows Susan’s magic horn. Once there, they help Caspian regain the throne and restore Narnia to its old and rightful self. (As an aside, the series in general is a lot more battle-y than I remembered – it’s interesting to note which elements stick in the mind and which don’t!)

There were three things which I particularly enjoyed in this rereading. There is a bit of theology in the third point, so if that’s not your thing feel free to finish reading at the end of point two.

1. The story within the story

Caspian’s back story is told to the children by Trumpkin the dwarf in chapters 4-7, making up around a quarter of the book. Katherine Langrish writing in From Spare Oom to War Drobe. Travels in Narnia with my Nine Year-Old Self says ‘the long backstory in the middle of the book is structurally awkward and takes us away from the Pevensies for too long.’ I disagree with her assessment here. When Trumpkin tells the children that it’s a long story, Lucy replies

All the better. We love stories.

I’m with Lucy. The four chapters of the story within the story move quickly and are a very useful way of showing Caspian’s childhood and bringing us and the Pevensies up to date with what’s been happening in Narnia. They also introduce one of my favourite characters, Caspian's tutor Doctor Cornelius, who seems to owe something to T.H. White’s Merlin from The Sword and The Stone (1938) but with rather less magic and more lessons.

Stories within stories are of course a classic literary device. I’d eventually find them in Nelly Dean telling the story of Cathy and Heathcliff to Lockwood in Wuthering Heights or in Gilbert Markham’s narrative which frames Helen’s diaries in The Tenant of Wildfell Hall. Grown-up stories but C.S. Lewis had helped their structure feel familiar.

2. The speed of time

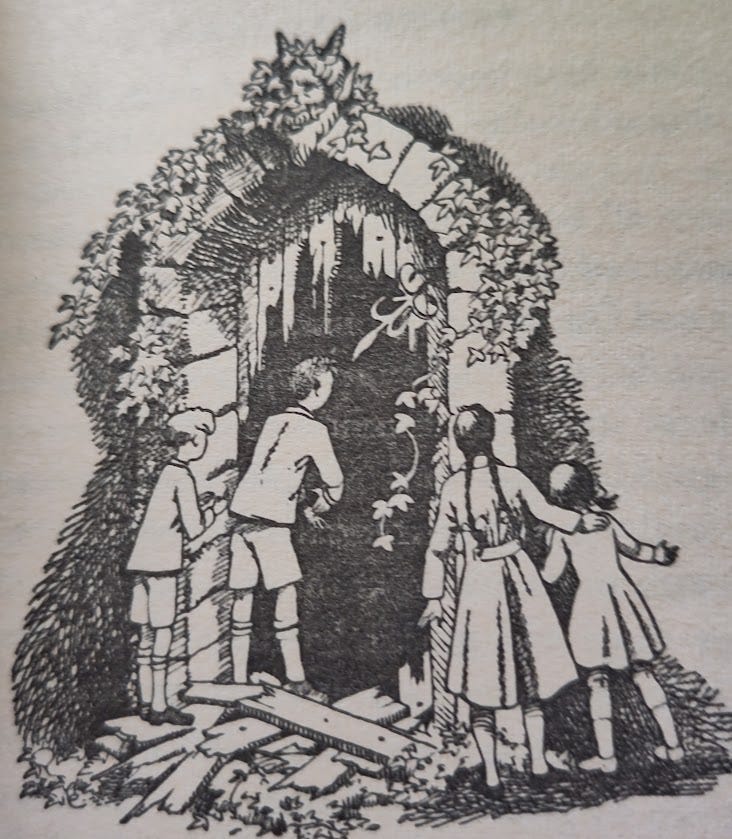

One of the most fascinating themes in Prince Caspian is time. We learn that time passes differently in Narnia and our world. On one level, we already knew this. At the end of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, the children return home having ruled in Narnia for years and find no time (or very little time) has passed at all. Here we see it the other way about. The children have spent a year of their own time away from Narnia but come back to find hundreds of years have passed. Lewis uses Cair Paravel to illustrate this point, their fine castle now lies in ruins – as Edmund puts it ‘Anyone can see that nobody has lived here for hundreds of years.’

As the truth dawns on the children, Peter says

And now we’re coming back to Narnia just as if we were Crusaders or Anglo-Saxons or Ancient Britons or someone coming back to modern England.

Slightly more philosophically, when Edmund and Peter encounter some wall carvings later in the story, Edmund asks

Look at the carvings on the walls. Don’t they look old? And yet we’re older than that. When we were last here, they hadn’t been made.

Even as an adult, thinking about that one makes my head hurt slightly! One of C.S. Lewis’ great strengths as a children’s author is the way he trusts children to engage with these kind of ideas and does so without patronising them.

3. Older and bigger

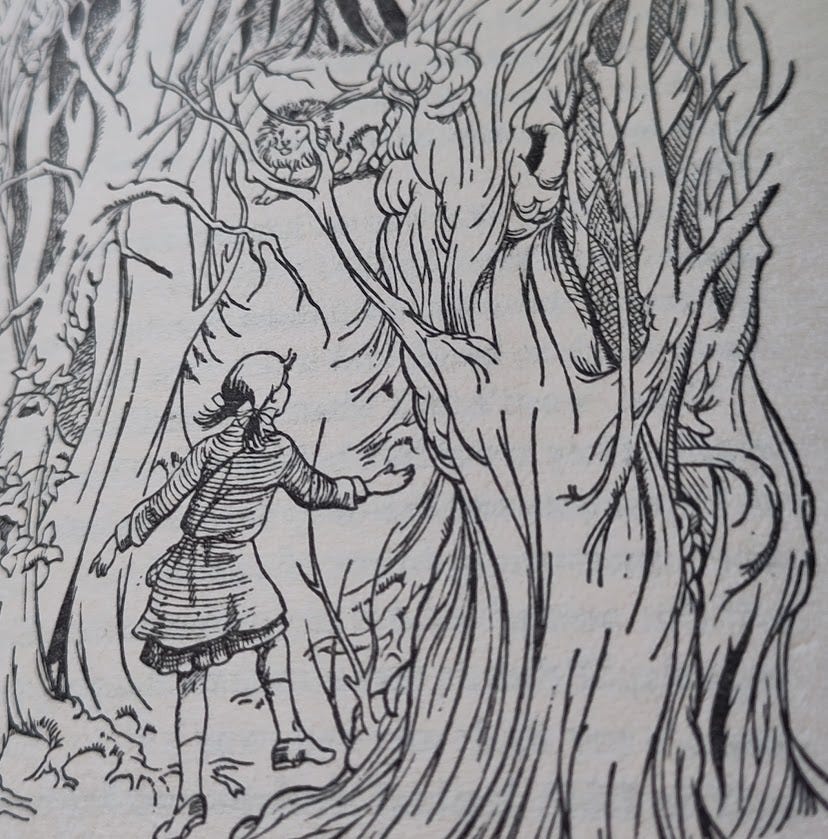

‘Aslan,’ said Lucy, ‘you’re bigger.’

‘That is because you are older little one,’ answered he.

‘Not because you are?’

‘I am not. But every year you grow, you will find me bigger.’

This is a lovely passage that subverts how we think about how perception changes as we age. It’s possible to over read Narnia in terms of Christian allegory but I think this passage bears some theological weight. If we read it as our understanding / conception of God should get bigger as we grow, then it acts as an important corrective to the habit of making God fit into ever smaller boxes of our own making. I reread Prince Caspian on Christmas Eve, a time of year when the Christmas story is packaged up neatly for children but when it’s worth asking whether the Christmas story grows with us? Do we appreciate the wonder and complexity of it more as we get older? And what do we lose in the process if the answer is no?

Once again, here is Lewis trusting his young readers with a big idea.

Coda

In a rather less profound way, I was amused by the last line of the book

‘Bother!’ said Edmund. ‘I’ve left my new torch in Narnia.’

which did rather put me in mind of Paul in 2 Timothy 4:13, when he realises he’s left his cloak and books behind and wants them retrieved.

Next month – Return to Narnia: part V – The Voyage of the Dawn Treader. What next for Caspian now he is king of Narnia?

Interesting post (again), and again it has me wondering… how do I, as a confirmed non-believer, approach the Narnia books? The allegory passed me by as a youngster, but now it's a bit hard to take.

Agreed about the story-within-a-story. I think people have got used to cinematic intercutting as the only way to tell overlapping stories, but in print there are so many other ways to achieve it. I particularly like the way Arthur Ransome will, when the characters get separated, have two chapters in a row that take place simultaneously. And of course Tolkien did the same thing with entire books of The Lord of the Rings!