Is there life beyond Bunyan?

Bedfordshire’s literary heritage.

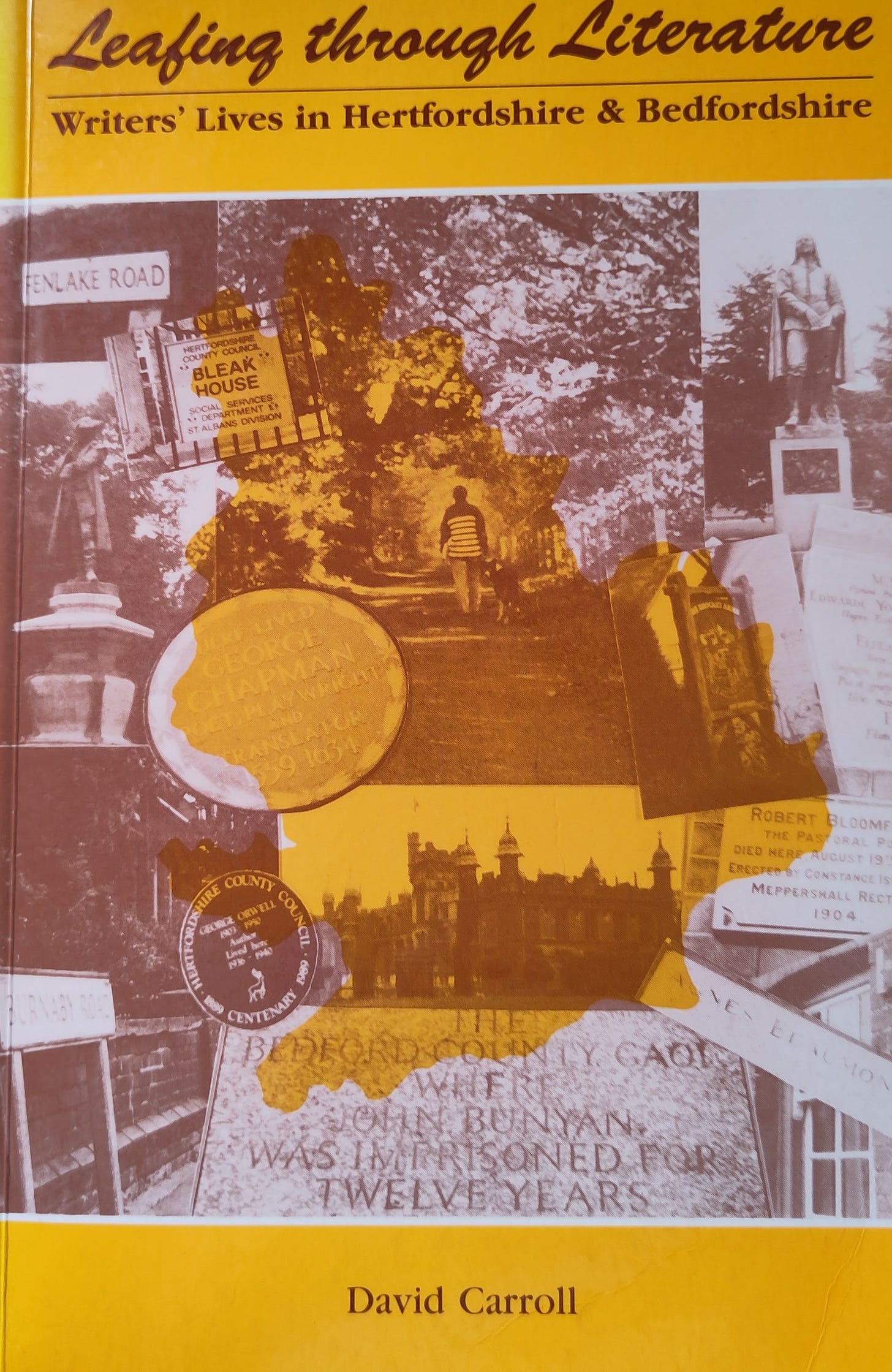

Idly browsing through our local second hand bookshop’s Bedfordshire section1 recently I came across ‘Leafing through Literature. Writers’ Lives in Hertfordshire and Bedfordshire.’ by David Carroll. It jumped out at me for two reasons, firstly because I’m always interested in writers and their homes and lives, and secondly because a year or so ago I wrote a piece on Bedfordshire’s literary landscapes as part of a themed series encouraging readers to explore the county, which was, to be frank, a bit of a struggle.

Name some counties or regions and the literary associations come thick and fast – the Lake District for example, or London or Cornwall, but Bedfordshire, if it’s associated with any writers at all, is John Bunyan country and not much else.

I got to six. Bunyan obviously. John Donne, who was Rector of Blunham (albeit a largely absent one) alongside writing poems and publishing his sermons. Robert Bloomfield, a pastoral poet in the vein of his contemporary John Clare but less well remembered. Mark Rutherford, born William Hale White, who wrote semi-autobiographical novels featuring Bedford, as well as literary criticism and other journalism. Mary Norton, the children’s author who gave us ‘The Borrowers’ series and the novels that would become Disney’s hit film ‘Bedknobs and Broomsticks.’ Kit Williams, who wrote and illustrated ‘Masquerade’ which led readers on a treasure hunt for a golden hare which turned out to be buried close to a Bedfordshire landmark. Carroll’s book includes the first four of these, his decision to exclude living authors meant the second two didn’t feature. (The book was published in July 1992, Mary Norton died later that summer.)

So, could Carroll’s book point me in new directions?

Of the 29 main chapters, ten covered Bedfordshire and 19 Hertfordshire. In addition there were three ‘loose ends’ chapters with shorter pieces, of these 11 featured Bedfordshire and four Hertfordshire. In theory the numbers end up about even across the two counties but in practice the weight lies in Hertfordshire. It has the lions share of the in-depth chapters and, whilst not entirely free from the stretching a point approach, the connections are much more solid. The writers are mainly familiar names – E.M. Forster, George Orwell, George Bernard Shaw, Beatrix Potter and Graham Greene all make an appearance.

By contrast, his ten Bedfordshire writers are:

Sir Albert Richardson – architect, magazine editor and writer. His books include ‘London Houses from 1660-1820’ and ‘The Art of Architecture’. He was also instrumental in the campaign to preserve the ruins of Houghton House (Bunyan’s ‘House Beautiful’)

Arnold Bennett – the writer is better associated with the Staffordshire potteries but lived in the village of Hockliffe on the A5 for a couple of years when he was looking for a rural escape from London. ‘Teresa of Watling Street’ dates from this period and evokes Hockliffe and the nearby Chiltern Hills, drawing on local people and their way of life.

Colonel Fred Burnaby – army officer, hot air balloonist, journalist and travel writer. His father was rector of St Peter’s Church in Bedford. ‘A Ride in Khiva’ (1876) was his account of a 3,000 mile journey through Central Asia, ‘On Horseback in Asia Minor’ was published in 1877.

Worthington George Smith – a botanical illustrator, specialising in fungi. He was also interested in archaeology and architecture, publishing ‘Dunstable: Its History and Surroundings’ in 1904.

John Howard – the prison reformer wrote ‘The State of the Prisons in England and Wales, and an Account of some Foreign Prisons and Hospitals’ in 1777.

Dorothy Osborne – over 70 of her letters to William Temple, who she would eventually marry despite opposition from both families, have been preserved.

George Gascoigne – a poet who wrote Masques to celebrate Elizabeth I’s progresses at Kenilworth and Woodstock.

Mark Rutherford, Robert Bloomfield and John Bunyan make up the list.

Amongst the ‘loose ends’ are John Donne, playwright Christopher Fry, poet laureate Nicholas Rowe who was born in Little Barford, and Horace Walpole who wrote the inscription for the monument to Katherine of Aragon in Ampthill Great Park. H.E. Bates (who was born in Rushden, just over the Northamptonshire border) is perhaps better associated with Kent and the Larkin family but also used some north Bedfordshire villages in his fiction, with his Great Uncle Joseph of Sharnbrook providing the model for Uncle Silas.

Despite Carroll’s best efforts, only Bunyan really stands up to close scrutiny and Bedfordshire is forced to share him with Hertfordshire in the book, as a separate chapter details his links with that county as an itinerant preacher. There are lots of interesting people mentioned but, in many cases, if they are known at all today, it’s not as writers.

Both the book and my own research left me wondering why Bedfordshire hasn’t inspired more writers, particularly in terms of fiction. Carroll makes a good case for both Arnold Bennett and H.E. Bates but downplays attempts to map the locations of events in ‘The Pilgrim’s Progress’ on to the Bedfordshire landscape. This is actually a fair point, as there is no contemporary evidence for it, but plenty of other writers including Vera Brittain have disagreed, stressing his familiarity with Bedfordshire as a likely source of topographical inspiration, whether consciously or unconsciously. Outside of Carroll’s remit, Mary Norton makes good use of Bedfordshire in ‘The Borrowers’ and I hope to come back to this in a future post.

It’s perhaps no surprise that Hertfordshire has been home to more writers – its close proximity to London is in its favour, but then Bedfordshire isn’t much further out and nor is it actually that much smaller (477 square miles to 634). Perhaps Bedfordshire’s eclectic mix of chalk downs, limestone villages, agricultural countryside and small market towns needed a Thomas Hardy kind of writer to put them on the literary map, while authors wanting to escape the capital looked for rural retreats in better known counties like Kent, Sussex or Norfolk.

In Sylvia Townsend Warner’s ‘Lolly Willowes’, the rural village of Great Mop that Lolly escapes to is in the Chilterns but I suspect the Buckinghamshire Chilterns not the Bedfordshire Chilterns, which somehow sums up the problem. As Lolly herself says, Bedfordshire is ‘the sort of county one sees from the train.’

Should you ever find yourself in Bedford with time to kill, take yourself to the Eagle Bookshop in St Peter’s Street.

I went to school in the house Mary Norton based The Borrowers on. Being a listed building meant very little had changed! I was always annoyed they had swapped the grandfather clock for a glass wall one!

Mary Norton's Borrowers also feature in the Studio Ghibli animé 'Arrietty' which is well worth watching. Though I guess not inspired by Bedfordshire locations.