The Voyage of the Dawn Treader picks up three years (in Narnian terms) after the events of Prince Caspian. Lucy and Edmund are staying with their cousin Eustace Scrubb, when all three are pulled into Narnia via a picture of the Dawn Treader. They join Caspian and his crew on an island hopping adventure to try and track down the seven lords of Narnia exiled by Caspian’s uncle, Miraz, following the death of Caspian’s father. Along the way they encounter dragons, sea serpents, slave traders, magic books and ponds that turn anything dipped in them into gold. Aslan puts in several appearances and eventually the children return home and Caspian returns from the voyage to rule Narnia.

I have to be honest – I wasn’t entirely gripped by this volume of the series and I’m not sure why because there are some lovely sequences. However, one of the things I did enjoy was the way C.S. Lewis drip feeds a kind of commentary on childhood reading.

As a boy, Lewis was a reader. In Surprised by Joy he mentions a wide range of books and stories – Edith Nesbit, Gulliver's Travels, Norse mythology, King Arthur, Beatrix Potter ‘and here at last beauty’, and classical mythology. From the library at school he borrowed poets like Yeats and Longfellow, and discovered Celtic mythology. Rooms are lovingly described as having ‘endless bookshelves’. From this reading came Lewis’ first writerly experiment ‘Animal-Land and, as he put it: ‘in mapping and chronicling Animal-Land I was training myself to be a novelist.’

As an adult, books continued to be important to Lewis in both his professional and private life. In 1954 the chair in Medieval and Renaissance English, a professorship in English Literature, was created for him at Cambridge University. In Surprised by Joy he wrote that ‘a young man who wishes to remain an atheist cannot be too careful in his reading’ when discussing G.K. Chesterton and other Christian writers.

Eustace’s reading habits

Very early on in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, in the second paragraph in fact, Eustace’s taste in books is described.

He liked books if they were books of information and had pictures of grain elevators or of fat foreign children doing exercises in model schools.

To a twenty first century reader that last bit is eyebrow raising to say the least, but the point being made is that Eustace is not a boy who reads stories. That point will be returned to throughout the book as a way of explaining both Eustace and his response to the situations he finds himself in. When he finds out that the punishment for stealing water on the ship is ‘two dozen’, Edmund has to explain what it means. Eustace writes in his diary that he didn’t know because ‘it comes in the sort of books those Pevensie kids read.’

The repercussions are greater when Edmund is separated from the others and encounters a dragon.

Edmund or Lucy or you would have recognised it at once but Eustace had read none of the right books.

The failure of his reading to prepare him for dragons is compounded when he finds the dragon’s lair.

Most of us know what we should expect to find in a dragon’s lair, but, as I said before, Eustace had only read the wrong books. They had a lot to say about exports and imports and governments and drains, but they were weak on dragons.’

I like this for the implication that different books tell us different kinds of truths, and restricting our reading restricts our ability to interpret the world around us. Lewis continues to hammer his point home when Eustace, transformed into a dragon, struggles to explain what has happened.

In the first place Eustace (never having read the right books) had no idea how to tell a story straight.

Writers must first be readers. This is Lewis’ own experience set down in print.

Edmund and detective stories

Lewis doesn’t directly spell out what kinds of books ‘those Pevensie kids’ read, although we can infer fairly easily that they include ships and dragons. The exception to this is when they encounter the armour of one of the exiled lords.

Edmund, the only one of the party who had read several detective stories, had meanwhile been thinking.

Edmund is puzzling out why there are no bones anywhere to be seen, the missing corpse is a plot device in more than one Golden Age crime fiction novel and here it’s employed in a rather different kind of setting.

An enemy might take the armour and leave the body. But who ever heard of a chap who’d won a fight carrying away a body and leaving the armour?

He’s right of course, and the logic he’s learned from detective stories sets them on the path to working out what has happened to the missing lord.

Lucy and the Magic Book

The one physical book in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader is a magic one. It belongs to a Magician (who else?) and Lucy must find the spell to make things visible again as part of their adventure with the Dufflepuds.

When Lewis describes the library he is surely conjuring up his childhood encounters with book lined rooms.

It was a large room with three big windows and it was lined from floor to ceiling with books; more books than Lucy had ever seen before, tiny little books, fat and dumpy books, and books bigger than any church Bible you have ever seen, all bound in leather and smelling old and learned and magical.

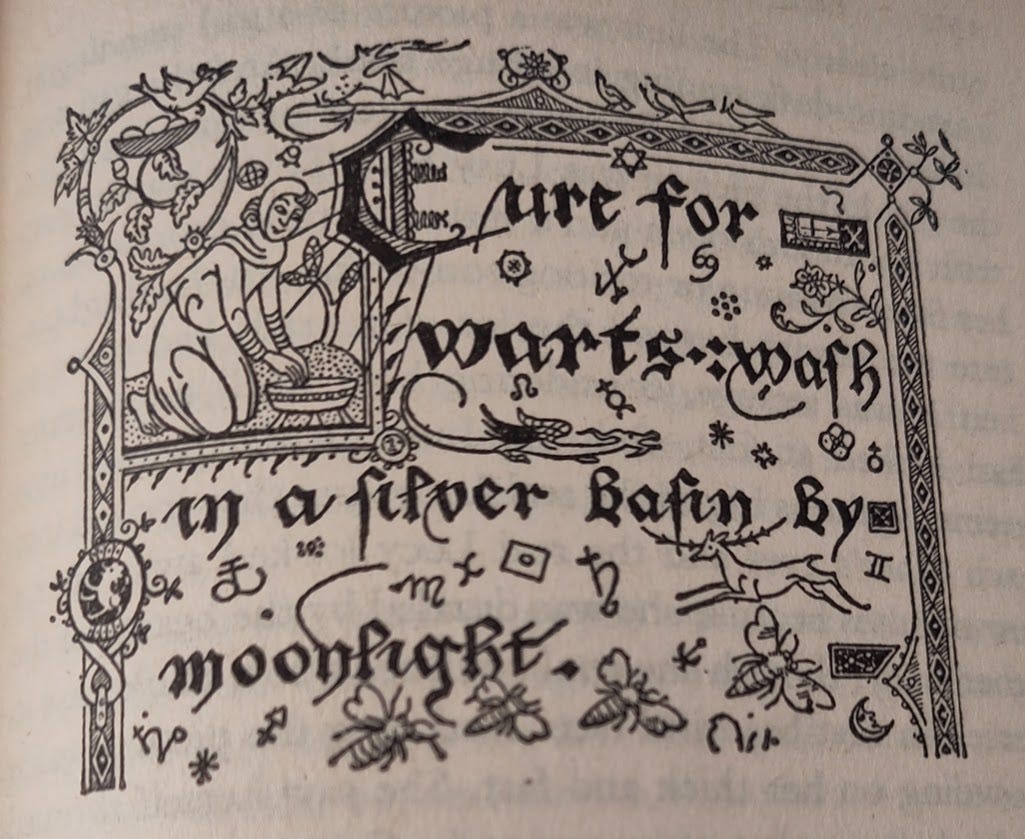

In the Magic Book, which sits on a reading desk in the middle of the room, there are cures for warts, toothaches and cramps, spells to find out what your friends think about you and a spell to produce an enchanted sleep. This is the stuff of fairy tales and Pauline Baynes’ illustration evokes a combination of a story book and a medieval illuminated book of hours.

Lucy finds that she can’t turn back the pages or remember the spells in the book but that the feeling of them somehow remains.

And ever since that day what Lucy means by a good story is a story that reminds her of the forgotten story in the Magician’s Book.

Lucy of course finds the spell and makes invisible things visible – including Aslan who makes one of his periodic appearances at this point.

One of the pleasures of returning to childhood favourites as an adult is noticing small themes like this one, which might well be missed by younger readers in the excitement of following the plot and the joy of spending time with familiar characters.

Next month – Return to Narnia: part VI – The Silver Chair

Oh, I love your point about the Golden Age mysteries! Never thought of it that way before.

This is one of my least favorite of all the Narnia books, for similar reasons, and also because all of the unsubtle, overt moral lesson-giving. (Though, to be fair, likely at least one bit of that lesson-giving — the part where Aslan explains why a friend might have said mean things behind one's back, out of fear — did make a deep impression when I first read it as a child.)

Reepicheep (sp?) is splendid in this one, however. Such a wonderful portrayal of gallantry and a genuinely curious mind.

I never liked this one much, I think maybe because I don't like the "dreadful child being brought to see the error of his ways" plotline. I prefer the books with a bunch or pair of children, all with strengths and weaknesses, working together with a lot of squabbling for a common end, rather than some unnaturally superior children (Edmund and Lucy) reforming a truly ghastly one (Eustace). I do love the Dufflepuds and the Magician's book though.